Preparing for a Pandemic

Written by Steve Sandstrom

Photography by Sara Way

A century ago, the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918 infected an estimated 500 million people worldwide —about one-third of Earth’s inhabitants — and killed between 20 million to 50 million people, including some 675,000 Americans.

Despite the advances of modern medicine, disease outbreaks that affect a large swath of the population have not been relegated to history. Last winter the flu hospitalized and killed more people in the United States than any seasonal influenza in decades. Nearly 80,000 people died from the respiratory illness, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

Andrew Wilber, PhD, associate professor of Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Cell Biology (MMICB), remembers the epidemic’s peak in January 2018. “Samples were coming in to all the state labs, hundreds every week. It was one of those times of great need when everyone has to step up. It was unprecedented, and our students were right there in the thick of it.”

The students he is referring to are enrolled in the Public Health Laboratory Science (PHLS) master’s degree program that Wilber directs, which offers experience in clinical, environmental and molecular testing protocols. It emphasizes versatility, preparedness and on-the-job training, qualities that raise the learner’s profile with potential employers.

Since 1980, the number of dangerous disease outbreaks per year has more than tripled. The American health care system may be the envy of the world, but it has yet to face a global pandemic. If an infectious disease spreads around the globe, could a medicine be designed and mass-produced in time to keep history from repeating? It’s a problem that requires a massive investment of scientific resources and people, and one which a program at SIU School of Medicine hopes to help resolve.

Understaffing Pressures

The nation is grappling with a shortfall in skilled lab workers dating back to the new millennium. In 2001, the CDC made recommendations to the U.S. Senate Appropriations Committee outlining specific goals that needed to be attained by 2010 to ensure a strong public health workforce. They stressed a need for epidemiologists, environmental health specialists and lab technicians.

In Springfield, administrators at the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) had begun to worry about the attrition rate among lab staff, many of whom were Baby Boomers. They needed trained staff who could not only take on the day-to-day tasks of a busy lab, but also had a master’s degree so that after a few years of experience they could assume supervisory roles.

To help meet this demand, the IDPH and Southern Illinois University School of Medicine (SIU SOM) worked together to create the Public Health Laboratory Sciences program in August 2005. This novel master’s program was the first of its kind at inception and is currently one of only three available in the country.

Despite the CDC’s urging, the U.S. public health workforce continues to be understaffed. Many factors are responsible: workers reaching retirement age or opting for early retirement as a consequence of pension reform; and a general lack of information to entice new graduates to pursue public health-related employment.

In addition, state and local budget cuts have resulted in a smaller workforce serving a growing population as lab testing procedures rapidly advance.

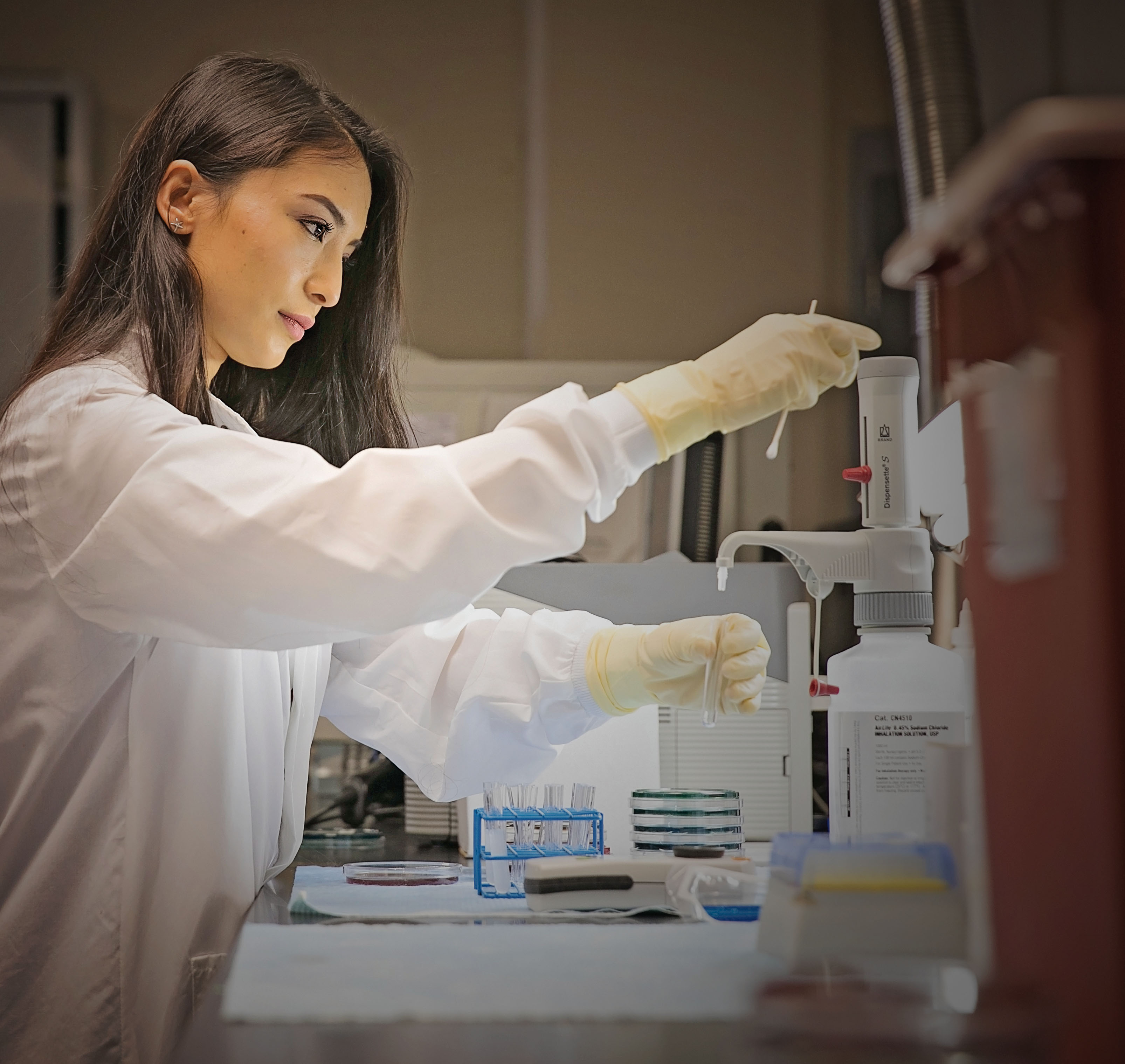

The two-year PHLS program combines graduate-level classroom instruction with extensive research experience in a public health laboratory. The objective is to produce scientists who can rigorously apply knowledge as they are cross-trained in a multitude of laboratory disciplines.

Academic coursework is supplemented with bench-top experience in the labs. Students learn testing procedures for clinical, environmental and bio-threat samples during routine, epidemic and pandemic events. In addition, PHLS graduate students meet Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (CLIA) certification requirements set by the federal government, which includes quality assurance and quality control procedures for record keeping, equipment maintenance, and experimental and environmental controls in each laboratory section — knowledge that is essential to work in any high complexity laboratory.

“The students are trained by experts, and once they’ve been assessed, they can effectively do the procedures and tests they need to do,” says Wilber. “They can work independently, and they have the advantage of being trained in more than one technical area of the lab. The older students are able to mentor the younger ones, sharing what they’ve learned while gaining managerial experience.”

The students have the opportunity to train on state-of-the-art equipment in three IDPH laboratories, in Springfield, Carbondale and Chicago. These labs perform different tests to support public health epidemiology programs throughout Illinois, and participate in numerous certification programs to ensure the accuracy of testing data. “The IDPH labs are some of the most technologically advanced in the U.S.,” says Wilber. “We are very fortunate to be able to train our students here.”

As the technology improves, the lab instruction has continuously evolved and grown to incorporate the new procedures. The fluidity gives the program an edge that benefits the students. “They learn a great deal, from the established to the latest technical advances, and they are prepared when it’s time for a job interview,” Wilber says.

Within the last year, the CDC has transitioned to a new bioinformatics testing phase that is another leap forward. Lab techs previously looked for specific changes in DNA fragments for the different bacteria responsible for enteric infections and other gastro intestinal diseases. Now they can sequence the entire genomes (all of the DNA) for each of these bacterial pathogens. The genetic sequence of a pathogen is its virtual fingerprint, which is why it is so effective in diagnosing a single person’s mystery illness. In addition to identifying bacteria, this technology can permit the CDC to appreciate other genetic changes that make bacteria more deadly or resistant to commonly used antibiotics.

By the end of the program, students have attained training in clinical, environmental and molecular testing protocols for infectious, sexually transmitted and heritable disease, as well as food, milk, water and blood lead testing. They also can aid in the identification of bio-threats as part of the Illinois Public Health Preparedness Center in collaboration with local and federal law enforcement agencies.

Once trained, the PHLS students can be deployed to increase the effectiveness of the public health services labs.

Some have a real affinity to the investigative mission. In 2010-11 the IDPH laboratory in Carbondale used the molecular expertise of PHLS graduate student Matt Gunkel to assist in the implementation of a molecular test for the identification of pandemic influenza, norovirus, HIV, Shiga-toxin (STX)-producing microbial pathogens, and bio-terror select agents. Not coincidentally, Gunkel was hired the following spring by the Carbondale IDPH in the Division of Labs, Office of Health Protection Laboratory.

As nature continues to produce new pathogens that infect populations and remind us of our human vulnerability, prevention and preparedness remain the linchpins of public health. Matt Charles, chief for the IDPH Division of Laboratories, believes that workforce training is crucial. “The right combination of education and technical expertise is essential to produce public health professionals who are competent to conduct clinical testing, train personnel and manage core public health facilities. We want these students filled with the skills to make society safer.”

First-year grad student Brianne Guzouskis considers the master’s program a challenging but invigorating stepping stone. “It’s the perfect balance of hands-on experience and curriculum to prepare us for any path we want to take as our next step into the science world,” she says.

While it has surpassed the expectations of faculty and students involved, the program has room to grow. And it needs more young applicants willing to prepare for careers “at the bench,” where science provides answers to issues of public health, and sometimes life and death.