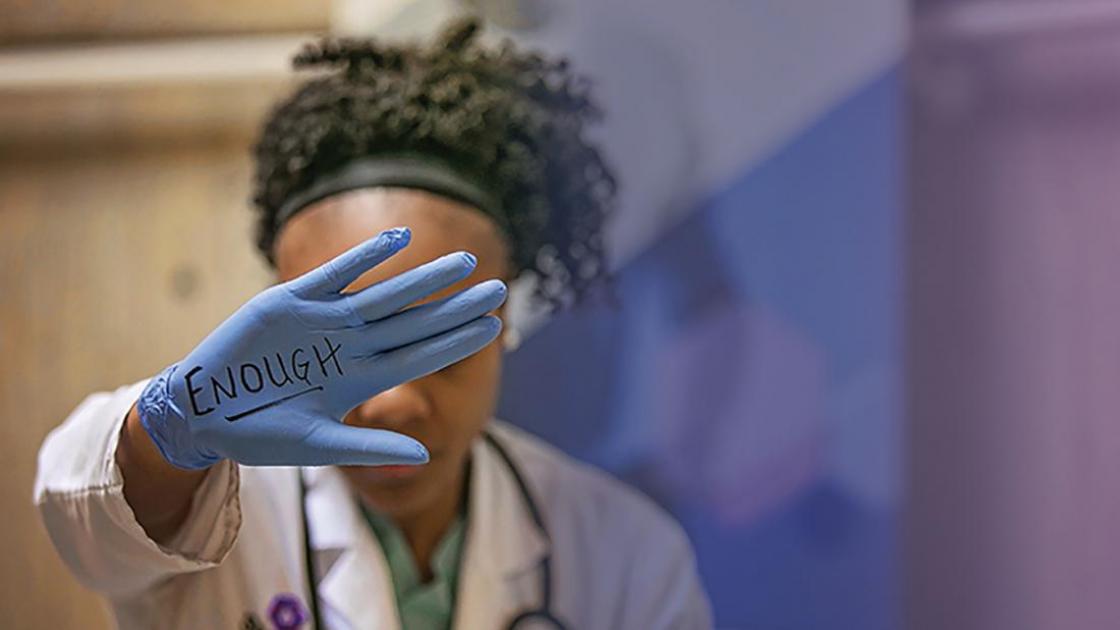

Critical Conditions: Training for Trauma and Violence at Work

by Steve Sandstrom

On an early Monday morning in March 2018, James Waymack, MD, was on his way to work at Taylorville Memorial Hospital. Waymack is the director of the emergency medicine residency program within SIU’s Department of Emergency Medicine, and on Mondays he accompanies a team of residents on a rural service rotation to a hospital 30 minutes east of Springfield. Nearing his exit, he was suddenly passed by three ambulances. Approaching the hospital, he found the parking lot teeming with police vehicles. Inside, emergency medicine director Rich Jeisy, MD, Waymack’s former SIU School of Medicine classmate, was providing care for the three gunshot victims who had just been transported from a nearby domestic violence crime scene. The law enforcement presence was there for protection, because the shooter was still at large.

That afternoon, officers spotted a man they believed to be the perpetrator driving on a rural Taylorville road. He had attempted to rob a convenience store in the interim. With the police in pursuit, the man drove into town and headed for the hospital. His truck struck the curb in front of Taylorville Memorial’s main entrance and came to a stop. The man got out carrying a pistol and headed toward the hospital door. When multiple officers confronted him and told him to drop his weapon, he shot himself in the head.

Dr. Waymack then found himself treating the man in the same nine-room ER where his victims had been receiving care earlier. The trio of victims—a man, a woman and a 13-year-old child—had been stabilized and transported to Memorial Medical Center in Springfield. With a life-threatening injury, the attacker was also stabilized and then sent to Springfield, where he died the following day.

SIU physicians, staff and hospital partners all receive training to prepare for active shooters and other threats. According to the Illinois Health and Hospital Association (IHA), physicians and clinical staff at hospitals across the state are trained in the “Run, Hide, Fight” response and use “plain language” and “color codes” to notify patients and staff of an incident. In addition, the IHA coordinates an annual Emergency Preparedness Exercise, giving hospitals the opportunity to rehearse for these harrowing incidents.

On Nov. 8, 2018, nearly 1,000 individuals participated in the IHA’s most recent statewide simulation. Different active-threat scenarios prompted teams to think through ways to keep patients and employees safe. Eleven days later, a domestic argument escalated into a triple homicide at Chicago’s Mercy Hospital and Medical Center, taking the lives of a doctor, a pharmacist and a police officer.

Both the Taylorville Memorial and Mercy Hospital tragedies demonstrate that no amount of preparation can guarantee total safety from workplace violence. But trained clinicians can help improve the odds of a safe environment for all.

Training for learners

Violence against health care workers—including verbal and physical assault—occurs in practically all care settings, with the highest number of recorded incidents taking place in psychiatric wards, emergency departments and visitor waiting rooms.

The Bureau of Labor Statistics classifies incidents of workplace violence as “intentional injury by other person” in its list of occupational injuries causing days away from work, and reported nearly 18,670 such injuries across the United States in 2017. People working in service occupations made up about half of the incidents (9,110). Health care practitioners and technical occupations reported the second-most: 3,130.

One of the ways SIU medical students are taught how to deal with aggressive and potentially dangerous patients is through clinical simulations with standardized patients (SPs). Since 1981, SPs have been used in Springfield’s Professional Development Lab to simulate real-life medical encounters students may one day face as physicians.

SIU medical students see their first SP during the first week of medical school. It emphasizes the importance of becoming comfortable with taking patient histories, performing examinations and polishing communication skills. As the clinical skills curriculum builds each year, the SP encounters become more complex.

A Doctoring Physician Attitude and Conduct session in year 2 centers on intimate partner violence (IPV). It includes information on the demographics of IPV in society, how doctors encounter it, and methods used to interact with and treat patients. Following the didactic, the students are split into small groups and exposed to one of two standardized patient encounters involving IPV.

In the current SP scenarios, a woman presents with persistent headaches and makes no mention of domestic violence. In the second, a loud and domineering spouse accompanies a female patient to her clinic visit. The student-physician has to figure out how to treat the patient for what could be IPV while the abuser is literally in the room. The second-year SP cases require the learner to discreetly navigate from suspicion to action.

When appropriate, a faculty observer will call a time-out and discuss ways to address the volatile situation. The students are also coached with techniques to de-escalate aggressive behavior. This includes choosing verbiage and empathy for how the patient is feeling, and ways to openly acknowledge the patient’s frustrations and fears.

In addition to skills learned through SP scenarios, SIU’s Departments of Family and Community Medicine, Medical Humanities, Pediatrics and Psychiatry offer Year 4 electives that address aspects of violence. Topics include vulnerable patients, biological terrorism response, health care responses to violence, the role of community service agencies, the criminal justice system and health disparities. The school also hosts frequent educational opportunities to spotlight concerns related to violence and trauma-informed care.

Training for frontline staff

Training nurses to deal with aggressive patients is a challenge which varies across clinics and departments. Jessica Barney, a nurse administrator in internal medicine, says that under very stressful conditions, “It’s important to try to stay calm, keep the patient calm and go find who’s in charge to take care of them. I tell my nurses ‘if it’s truly dangerous, just try to get yourself out of the room quickly and call Security. Then come find me.’”

Catie Myers, an SIU charge nurse in the Department of Cardiology says, “For a new nurse, any kind of confrontation with a patient is overwhelming. Through the years, I’ve found that de-escalation is the key to getting the situation under control, whether it’s on the phone or in the clinic.”

Nurse educator Leslie Montgomery and the nurses interviewed for this article all see the value in a debriefing conversation when a traumatic episode or death occurs in a “code session.” This gives the care providers time to reflect and acknowledge what they experienced. Connecting with other care providers afterward and talking with nurse managers was a standard operating procedure mentioned within the group. “You can lean on your peers,” Montgomery says. “After that, I would go home and talk to my family. Venting to my husband was my usual debriefing.”

She recommends debriefing sessions be made mandatory under certain circumstances, so nurses wouldn’t have the option of toughing it out and regretting it later. It could remove some of the stigma from requesting the counseling opportunity. “Our days are so busy,” she says. “Sometimes you won’t even know how much something has affected you until much later.”

Emergency room trauma

When a critical incident occurs, an otherwise healthy individual’s coping skills can be shaken. After providing care, it is vital for clinicians to have the space to process their emotions about violence.

Dr. Rich Jeisy remembers the shock and trauma that he felt after treating patients in the triple shooting at Taylorville Memorial Hospital’s Emergency Department in March 2018. Afterward, he was simply staring at his computer. “I needed to chart but didn’t feel like I could focus,” says Jeisy. “All of the emotion of the last two hours seemed to come crashing down.”

Jeisy had been working an overnight when the countywide EMS radio went off, calling for response to a gunshot wound. While examining a patient for a general illness, Jeisy recalls the traumatic scene and sequence of events:

I was examining the patient when there was a commotion at the ambulance door. One of the nurses opened the door, and a firefighter walked in with two patients with gunshot wounds. They were immediately taken to our two trauma rooms with nurses taking each one. I quickly left the patient I was seeing and attended to the more seriously wounded patient. When I determined that patient was stable, I moved to the other. As I bounced back and forth between the two rooms, we received a call from EMS. They were on the scene and had a patient with a gunshot wound to the head. Amazingly, that patient was alert and responsive. I knew that we would need one of the trauma rooms, so we quickly moved one of the other patients. At the same time, our charge nurse and I declared a mass casualty event.

Jeisy says he could not be more proud of the nurses and techs who were in the ED that day.

“They did an amazing job of focusing on patient care and keeping the patients calm during a hectic situation,” he says. “They were all business and did a great job of ignoring the emotional aspect of this until everything else was done.”

Jeisy says he felt fortunate he was able to discuss the incident with his colleague and SIU classmate, Dr. James Waymack—“someone who understood the situation from a physician standpoint”—at the shift change. He then headed home to explain everything to his wife.

“Talking about it with someone who knows me so well was equally helpful,” he says.

With the nature of the work and long hours, emergency care faculty are especially watchful for how post-traumatic stress affects staff, Waymack says. Whenever necessary, a huddle or debrief will be called to capture the team that experiences a critical incident, so they can talk about everything and do immediate post-processing.

John Sutyak, MD, associate professor of surgery and director of the Southern Illinois Trauma Center, appreciates that residents have counseling available. “And we make certain they have a support system in place and encourage them to take time to care for themselves,” he says.

In addition to counseling and conversations with coworkers and family members, other popular stress relief options for health care employees include:

- listening to music

- getting sufficient sleep

- eating with nutrition in mind, minimizing sugar and caffeine

- avoiding alcohol and drug use

- exercise, especially when alternated with relaxation

Both Waymack and Sutyak endorse exercise as a practical prescription. “When your mind’s not right, focus on your body,” Waymack said. But the crucial element is for the healer to recognize that he or she needs healing, and then to actively pursue it.

Excerpted from Aspects magazine, Spring 2019